#41 The Black Art of DevOps

Subscribe to get the latest

on Tue Mar 09 2021 16:00:00 GMT-0800 (Pacific Standard Time)

with Darren W Pulsipher,

Darren Pulsipher, Chief Solution Architect, Public Sector, Intel, defines common DevOps terms and explains where DevOps fits into your organization.

Keywords

#devops #people #technology #compute #devsecops #cybersecurity #multicloud

Listen Here

Let’s take a look at where DevOps fits into your infrastructure.

At the bottom of a normal stack, we have a physical layer which could mean a cloud, data center, IOT devices, or legacy infrastructure.

On top of that, there is normally a software-defined infrastructure that abstracts away the complexity of managing the individual pieces of hardware.

Next is a service management layer, which includes the container ecosystem virtualization and a distributed information management layer, which includes the data plane, data lakes, and everything managing your data.

Then comes the application layer. Application developers use the services inside the application layers. Right at the interface between the application layer and the data management plane and service management are the SecDevOps or DevOps toolkit. These tools include security and identity aspects that provide a secure way of continuously integrating and deploying your products.

Application / Workload Layer

At the top of the application and workload layer that feeds SecDevOps are three types of workloads: event-driven workloads, procedural workloads, and a hybrid of the two, which are GUI- or UI-driven workloads.

A simple example of an event-driven workload would be that a purchase order arrives in your system causing other things to happen. There can be sequential or parallel steps, interaction with humans, and automation and interaction with several different applications or subsystems within the company.

Many workload automation tools are available. Some are scripted and some use robotic process automation, which are more GUI- and UI- driven. These tools work on the automation of services underneath, so the workloads drive service interaction.

Services traditionally fall into three major categories: applications, such as off-the-shelf products like Word or an SAP application; complex services, which are built for a specific purpose, such as a MEAN stack with Mongo; and simple services, which do one thing, for example MongoDB which stores the database.

There is a new category because of the growth of AI and ML. A lot of services don’t do much without a model attached to it, so we’ve added AI models in to the service layer, which we treat much as we would a simple service.

Developer Day in the Life

After we understand the workloads and services, we can look at what a developer typically does.

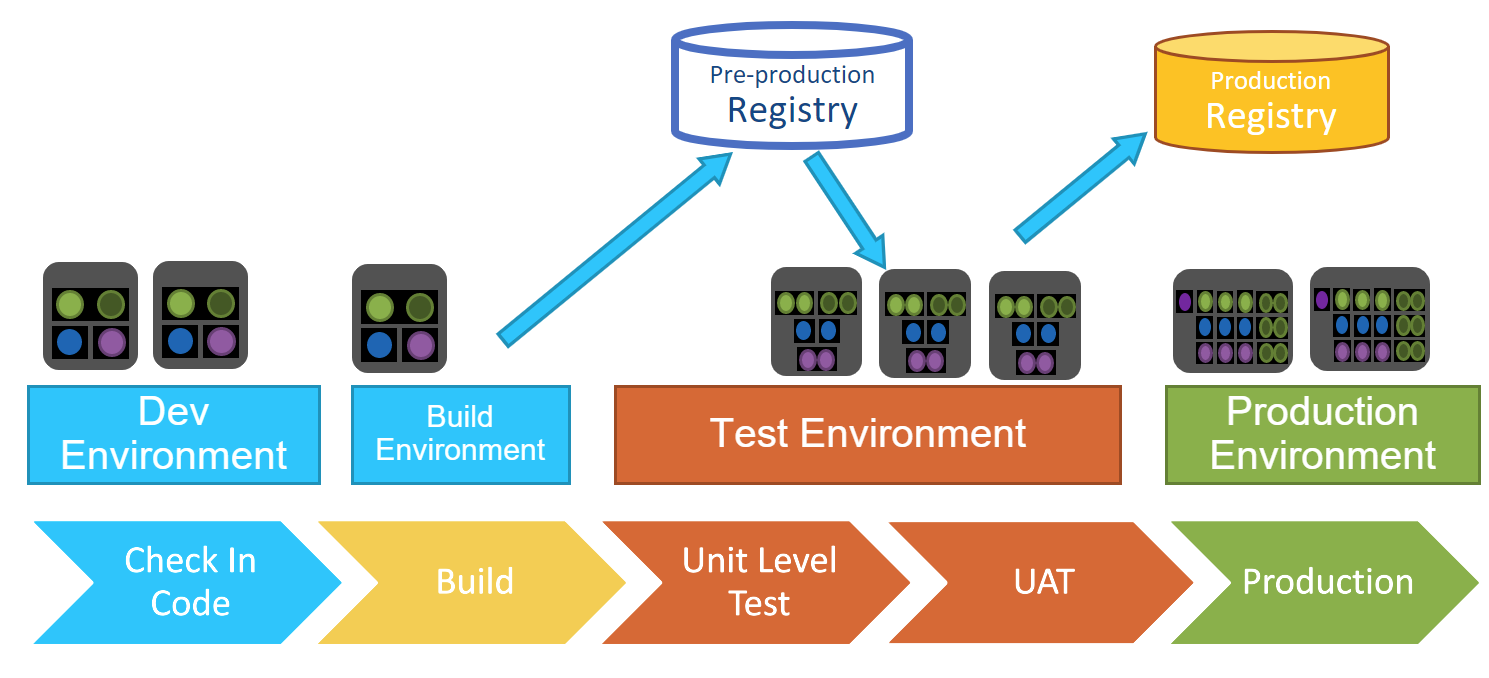

A developer will write some code on their workstation and run a few functionality tests. Then they check the code into GitHub, for example, and a continuous integration continuous delivery (CICD) pipeline kicks off. It runs security checks against the code, perhaps lint, static analysis, and dynamic analysis.

Once it passes those tests, it will usually check into an integration branch where other people on the development team grab the data and develop it and integrate their code with the developer’s code. Then, when it has passed their tests, it is pushed out into a test stage. Once through that stage, it will go into production.

This is a typical CICD pipeline, which has been around for decades. Over the years, the different ways of describing pipelines has been consolidated and standardized, limiting complexities and errors.

DevSecOps Stack

The pipeline is only one element of a SecDevOps stack.

Other necessary elements include a registry and a repository. Think of these as versioned repositories to keep artifacts that are generated during the CICD pipeline so they are easily available to use over and over again.

Another important element is an automation framework. This helps to alleviate the human labor of running tasks such as security checks or promoting builds from one stage to another. The tools for automation are mature and training is available, so a good automation framework should be fundamental.

Although environment management often grows organically over time, it makes sense to manage and architect the environments appropriately to get more reliability and repeatability.

A key element underneath it all is a security profile. You should be able to have the ability to define security profiles, so that they can be used in multiple environments and across multiple application stacks.

Registries / Repositories

There are usually at least two different types of repositories. The first is a staging repository, where you can generate images (a gathering of all the code that’s needed in order to spin up a container, for example), and store things like identity and secret keys. This repository contains everything you need to move things into production. Some organizations may have multiple staging repositories as different elements move through different stages of maturity until they reach the production repository. You want to be able to go back to previous versions if necessary.

In the production, or golden, repository, images are locked down, notarized, and encrypted. Only things in the golden repository every get moved into production.

Stages

The best way to think of stages in the CICD pipeline is that each stage works in a single environment. For example, in a build stage, there is a contained build environment with policies. Only when all the steps in this stage are accomplished can things move to the next stage. This avoids chewing up resources with parallel builds and runs that may ultimately fail. At the same time, it’s best not to have so many stages that they hamper progress, so a careful, defined plan is important.

Steps

Inside the stages are steps where the work actually gets done. In building and testing software, steps can be run in parallel or sequence; there are many tools that allow you to define these operations. Although some have a GUI for this, most developers prefer a textual format because it enables version control of the pipeline and steps, allowing security checks against the pipeline.

Pipeline

With stages and steps defined, you have a real pipeline. Instead of defining one pipeline for all of your applications, which typically fails because it becomes overly complex with a lot of conditions or too restrictive, I recommend using template pipelines and modifying as necessary, making sure they adhere to compliance standards and regulations. Getting an appropriate pipeline established at the beginning of a project is important, as is flexibility as the project progresses.

Environments

Instead of creating ad hoc environments, it’s best to create them with intention up front. DevOps or SecDevOps can inject security policies and compliance across all the different projects, ensuring security.

Service Stack

Let’s look at how developers work, which is on services nowadays. Even if developers are working in a monolithic application, they tend to group their work into a functional units like databases, business logic nodes, or transport layers. For example, using a simple service such as MongoDB. When a developer runs that container on their laptop, it gives them the functionality they expect to store data in a non-SQL way in a document. On the laptop, It may be the only container running.

In a test or dev environment, there could be multiple instances of that service running, and the developer may deploy a cluster of MongoDB services and connect them together for a test. The service is still a Mongo DB service, but its behavior changes based on the environment that it’s in. The goal for developers is to write code and check it in against the MongoDB service on their laptops to guarantee it will run all right in production.

A simple service like MongoDB is necessary, but by itself, not very useful. Complex services such as LAMP stacks or MEAN stacks are more important. These are multiple services running together, acting as basically one service. Bundled together, this deploys a complex service on a laptop and there are two or three simple service containers that are running, giving developers the necessary functionality to check in their code.

Once the code is checked in, it kicks off into the development pipeline where the developer is integrating with other people. The same complex service can take on a whole different way of doing things. Many security policies can be attached to that complex service to help make sure it’s secure, reliable, and resilient.

Service/Application Definitions

It’s important to understand the concepts of simple and complex services because software developers must define how to get them to work. There are a few definitions. One is called an image definition. These are frequently in the container world, called Docker images. The Docker file defines what is in that image. This is considered a simple container by itself, although people are starting to use containers for complex things.

Within service definitions, we can include multiple imagine definitions, for example, Docker Compose, Kubernetes Operators, Helm Charts, Terraform, and even CNAB. These are tools that let you define a service. A service is more than just the container; it’s the environment in which the container is running. It could include network definitions, volume connectivity, or even deployment policies. A complete “service definition” has image, configuration, and provision definitions.

Putting it all Together

When a developer is creating a new service, they’re not just developing the code for the image; they are also defining the environment, or configuration, in which it needs to run. This is where the mesh of your environment and the service definition can come together. At run time, it will produce the environment that is needed in order for the container to run effectively in a repeatable manner, so that you can easily move code from running on a desktop to running in full production as quickly as possible.