#35 Navigating Disruptive Change

Subscribe to get the latest

on 2021-01-13 00:00:00 +0000

with Darren W Pulsipher, Rick Herrmann,

In this episode, Darren Pulsipher, Chief Solution Architect, Public Sector, and Rick Hermann, Director US Public Sector, Intel, discuss how Intel has been successful in navigating disruptive change over the past three decades.

Keywords

#businessmanagement #disruption #generativeai #people

Rick recently celebrated his third decade at Intel, and in that time, he helped Intel navigate through tremendous amounts of change and big events. Along with tough competitive situations and industry change beginning with the rise of the internet and the dot.com boom and bust, there were external events such as 9/11, the Great Recession, and now, the COVID-19 pandemic.

Types of Crisis Situations

The nature of a modern enterprise in a modern economy is that it will be constantly navigating a high degree of uncertainty, turmoil, change, and disruption. Organizations either wither in those moments or come out better and stronger.

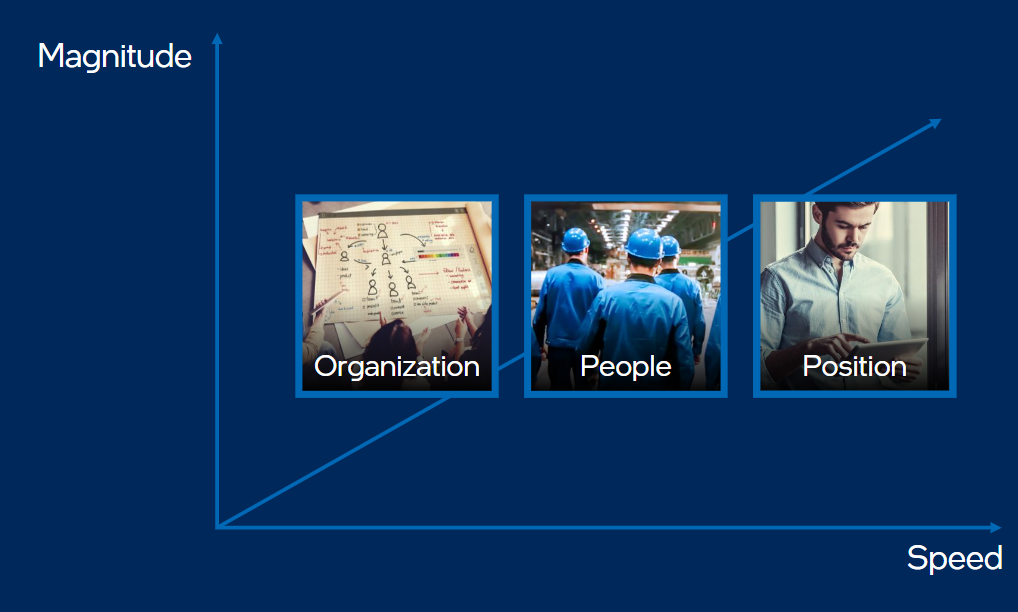

Every disruption is different in terms of magnitude and speed. Some events unfold over a long period of time, perhaps a technological or structural change in the industry, and then suddenly accelerate. Some, such as COVID, are high impact at unprecedented speed. What’s interesting about COVID, however, is we have been developing the technology to deal with the consequences of the pandemic for a decade, but it took this event to put it into practical use. A good example is telehealth. Its sudden, widespread use has also changed the policy environment, and the healthcare landscape will never be the same.

This type of fundamental change in policy happens in events with great speed such the Great Recession or 9/11. Similar things will happen post-COVID. These events, as difficult as they are, provide an opportunity for organizations to take a giant leap forward in how they perform and how they use technology.

Navigating Disruptive Change

Intel has always stepped forward in responding to big challenges and disruptions. Fundamental parts of the culture are readiness, shared purpose, and trust. These can exist when employees have a sense of psychological safety. For example, Darren felt empowered when Intel’s CEO said that no on would be laid off because of COVID. This allowed him to take risks to meet the crisis without any fear of losing his job. And although the CEO and senior manager set the tone, most of the work of psychological safety is carried out by the frontline managers. This safety and empowerment leads to a built-in readiness. Along with shared purpose and trust, these are the fundamental building blocks of not just an organization ready to respond to a crisis, but the characteristics of a high-performing organization.

A high-performing organization will also have the tools to navigate disruptions that are more of a slow burn rather than a fast, high impact event. With events like COVID or the Great Recession, there’s very little debate about what is happening, and everyone is onboard with the enormity of the issues. If you compare that to, say, a fundamental business shift, an architectural shift, or a technology manifesting on the hype curve that you’re not sure is material to the business yet, there will be more uncertainty and debate about the adjustments.

How does an organization survive these inflection points? Telemetry, or the input you are assessing, is important. One of the complexities in a big organization is that by the time these inputs get to a senior decision-maker, they may have been through three layers of massaging and positioning, and that can be dangerous. Truth and transparency is a value at Intel. In a company with a high degree of psychological safety, employees can speak the truth about problems.

The most important input is listening to your customers because they will tend to lead you in the right direction. For example, if someone wants to know about an account, Rick will often bring in the account executive to get the frontline information. It’s also wise leadership to go directly to the experts instead of getting information through three layers of filtering and massaging, especially when operating in a crisis. Meeting the moment boils down to readiness culture, the right telemetry, and decision making.

Decision making can become convoluted in a large organization. One simple solution is that every person walking in to a meeting should be asking, are we here to make a decision? Who is the decision maker? Or, are we simply debating or preparing the telemetry and data for a decision maker? This is just good organizational hygiene.

Andy Grove said, “Let a little chaos reign and then rein in the chaos.” For decisions on the inflection points, the slow burns, sometimes you have to let innovation breathe and percolate a bit, and at the same time you want to manage things in such a way that they don’t careen out of control. Having good processes and guardrails in place helps with this.

In difficult times, decision makers need to have a deep understanding that individuals are each going to be in a different space, and they have to think through the impact of decisions. Psychological safety is so important, and the frontline and second line managers are critical to the ability of an organization to execute well in time of disruption. Senior leadership is key in setting the tone, but these managers shoulder the work.

From predictable future technological changes such as the impact of AI on 5G, to problems like climate change, to unanticipated world events, the only constant is that we will always be navigating disruption, crises, and change. One of the hallmarks of Intel’s culture is its ability to respond, to adapt, and to be resilient to these events.